ElevateNext 2020 Vision Series: Ken Grady Interview

December 13, 2019

We had a great response to our initial post in the ElevateNext 2020 Vision Blog series featuring Susan Hackett. As a reminder, we’re asking legal industry visionaries to use their “2020 vision” to predict what the industry will look like in 2025 in the form of answers to four questions. We know this next instalment featuring Kenneth Grady will not disappoint. Ken has a knack for bringing a remarkably unique perspective to the table and explaining it in such a way that will make you realize how obvious that perspective should have been all along. We welcome comments, feedback and, of course liberal sharing. Enjoy.

~ Nicole Auerbach & Patrick Lamb

Founders, ElevateNext

Interview with Ken Grady

Ken Grady

Author, Professor & Legal Future Evangelist; Elevate Advisory Board Member

Q: What do you predict will be the two biggest changes in the legal profession as of 2025 and why?

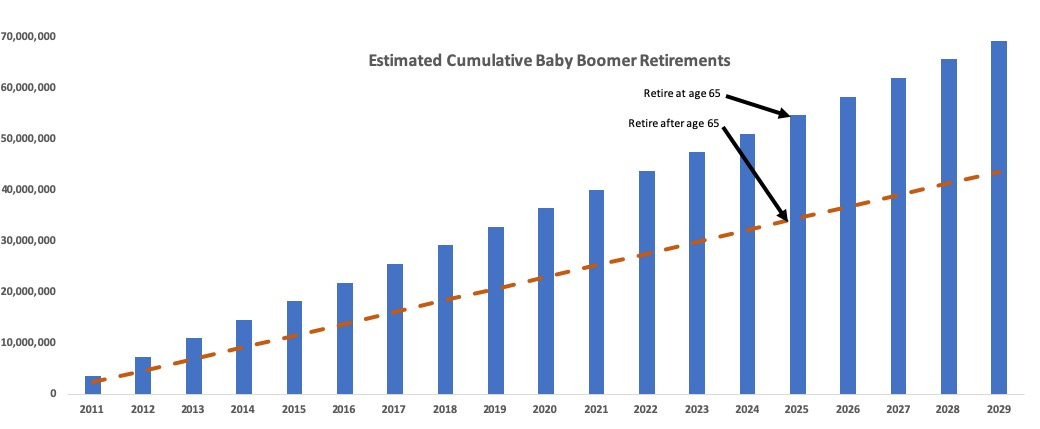

My first prediction involves the Baby Boomer challenge to law firms. Baby Boomers were born in the period 1946 to 1964 and started retiring in 2011. Assuming all retired by age 65, the last Baby Boomer would retire in 2029. In reality, we know some Baby Boomers retire after age 65 – statistics show about 37%. This is what a chart of Baby Boomer retirements looks like using age 65 and after age 65 (10,000 reach age 65 each day):

By the end of 2025, 79% of Baby Boomers would have retired if they retired at age 65. If they continue to delay retirement at the current rate, about 50% will retire by 2025. According to ALM Intelligence, as of 2017 in the 400 largest U.S. law firms 22% of lawyers were Baby Boomers. But Baby Boomers made up 40% of partners. We can predict that the 40% will drop to 20% or below by the end of 2025 if Boomers continue pushing retirement past age 65.

The impact of these retirements will vary by firm. But, if we consider the effect of the retirements as a group, I predict the implications are great for the law firms and the clients that use them:

- A significant amount of paid-in capital will leave firms by the end of 2025 and, equally, firms will need a significant influx of paid-in capital. Unless firms are prepared to shrink or remaining equity partners want to kick in more capital, this should affect future equity partnership classes. At the same time, many are warning against becoming an equity partner. Doing so now and paying in capital could be, in many firms, like buying stock at a high price just before the recession.

- Firms will lose an enormous amount of tacit knowledge (“skills, ideas and experiences that people have in their minds and are, therefore, difficult to access because it is often not codified and may not necessarily be easily expressed”). The lost tacit knowledge includes information about, and matters handled for clients. That knowledge can give a firm an edge when competing for business, so the loss of that knowledge can be painful.

- Equity partners usually control the majority (by revenue) of client relationships. Changeover in equity partnership ranks means many of those relationships (some of which have been long-term) will be transferred to others in the firm or go away. As the bonds between firms and clients loosen (and they already have loosened) clients may feel freer to look at other service providers.

- In-house counsel should be ready to answer: “What is your Plan B?” Law firms are fragile, expensive institutions. If equity partner turnover accelerates, the pace of law firm mergers (or, shudder, dissolution) may accelerate (hard to believe). At a minimum, if in-house counsel relied on Baby Boomers, those lawyers will be going away. Plan B should be a robust strategy for dealing with change.

- Finally, and this may have escaped attention, the generations that come after Baby Boomers have different priorities than Baby Boomers. Just as those generational differences have effects on society as a whole, they have effects on law firms and on the legal industry. Law firms run by and staffed by individuals outside the Baby Boomer generation may be very different than those companies have gotten used to over decades.

My second prediction involves the sea-change in the trust people place in core institutions that have dominated our lives since World War II. Governments, churches, universities, businesses, and yes, even legal institutions have experienced declines in trust. For example, according to Gallup polls 62% of people in the U.S. approved of the “way the U.S. Supreme Court is handling its job” in 2000. By 2012, the percentage approving had dropped to 46%, though it has since rebounded to 51%. Again, according to a 2018 Gallup poll, asked how much confidence people placed in various institutions, 37% said they placed a great deal or quite a lot of confidence in the Supreme Court and only 22% placed such confidence in the criminal justice system. Confidence levels go up and down driven by many factors, but the trend of declining confidence in institutions continues.

The declines in trust have a direct impact on legal services delivery. As but one example, consider what is happening with arbitration as an alternative to litigation. As trust in courts has declined and arbitration (supported by the Supreme Court) has risen, the number of disputes which go through courts drops. That impacts the evolution of the law in a common law system. It also can impact the precision of predictions about case outcomes. It changes the cost of dispute resolution and can alter the calculus of parties when deciding to pursue or defend claims.

I predict that the volatility and unpredictability of risk associated with legal services delivery will increase as trust in institutions remains low. The greater the margin for error in predicting what the opposing party will do in the event of a dispute and the less confidence there exists in those institutions involved in disputes, the greater the risk associated with various forms of legal service delivery. Prediction models, whether analog or Artificial Intelligence, are based on past outcomes. If the present and future do not look like the past, it will be more difficult to predict risk. Past performance does not guarantee future results, and with increased variability it may be a poor predictor of future results.

Q: What should be the biggest change as of 2025 but won’t be?

Over several decades, the legal profession has moved from strategic thought to mastery of technical detail. In my view, that shift drove profits, but not respect. It has had negative consequences for lawyers, clients, and society.

Lawyers face increasing stress as they try to thread the needle of compliance in a vastly expanding universe of regulatory complexity. At the same time, they sacrifice broad picture thinking that humans can do, and computers still cannot. Clients pay the price. They lose the benefit of individuals trained in critical analysis who can step back from day-to-day battles and consider questions in a larger context. They also lose the moral compass thinking that comes with a broader perspective. Society suffers because one of the traditional gatekeepers for institutions has stepped out of that role.

Many call for lawyers who work for or with institutions to think of themselves as businesspeople, but with a focus on law (just as others focus on marketing, finance, or operations). Making that shift, coupled with the focus on technical rather than big picture, has deprecated the role of lawyer.

The shift for 2025 should be a move back towards what lawyers can do: be the gatekeepers and statesmen and women for institutions evolving to function in a new world of challenges. Lawyers should think of themselves as lawyers, but with a deep understanding of business and an ability to provide legal services efficiently, at high quality, and reasonable cost.

As I write this, major scandals and legal problems grip the airline industry, tech companies, and academia. As long as people run institutions, there will be scandals. In one scandal, a lawyer is at the heart of the wrongdoing. But all of the existing scandals raise the same question: Where were the individuals who counsel the leaders in these organizations? That is the role where the lawyer qua lawyer versus the lawyer qua businessperson should dominate.

Counseling institutions can be tough, whether doing so from the inside or the outside. In this time of change, when an increasing number of people expect institutions to act for the benefit of people, not just financial stakeholders, having individuals who see and are seen as articulating the broader picture becomes more important.

Q: If you could design something that does not exist right now that you think would be of help to you or the industry in 2025, what would it be?

I want an information scoop and filter. The volume of information generated each day is almost beyond comprehension and that volume continues to increase. To make informed decisions, we need ways to scoop up information and then filter it for relevance. The broader the portfolio we manage, the more difficult it becomes to do this using the tools currently available. Getting a flood of newsletters in your inbox telling you that last week a new law was enacted does not help when the time to make changes was before the new law. To have a broad perspective, we must be able to get the nuggets of information we need to counsel clients without spending hours sifting through the irrelevant. We can use the saved time to build knowledge in those areas that help us think strategically.

Q: If the current you could give advice to the future you about anything (doesn’t have to be law-related), what would it be?

Step back, breathe, and take time. I came of age as a lawyer in a time when the tempo of delivery of legal services increased rapidly. We moved from typewriters to computers and from snail mail to email then to instant messaging. As the tempo has continued increasing, the expectations of others and our expectations for ourselves have changed. Instantaneous decision-making is expected, because we have the ability to share information instantaneously. But the processing power of the human brain has not changed in the past 40 years. When all around you are racing, take the time to be the calm center of the vortex.

Back to Expertise